|

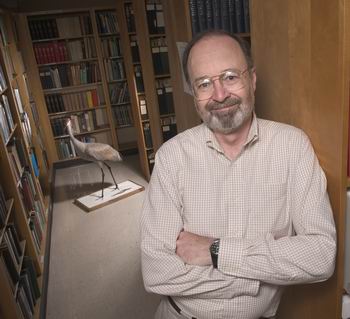

| Stanley A. Temple |

Stanley A. Temple worries that however well-intentioned it might be, the reintroduction of extinct species could have unintended consequences.

"We could actually end up with a net loss of biodiversity," Temple told several hundred scientists and conservationists on March 15 in Washington, D.C., at a high-profile symposium on the science and ethics of reviving species that no longer exist.

Temple is a professor emeritus at UW. For 32 years, he had the same position once held by Aldo Leopold, who is widely regarded as the father of modern wildlife management.

Temple has spent his career helping to protect and reintroduce endangered species. He's been involved in projects in 21 countries. In Wisconsin, his research has included efforts to help reintroduce the peregrine falcon, trumpeter swan and whooping crane.

Now, scientists are working on an entirely new strategy that goes beyond the current approach of building up the size of a species from a small resident population.

It's a process known as "de-extinction" and the genomic research that lies at the heart of it is much closer to reality today than the science fiction of dinosaurs stomping across the island laboratory depicted in the "Jurassic Park" movies.

In 2003, scientists from Spain and France brought back from extinction a wild goat known as a Pyrenean ibex by harnessing cells from a preserved specimen. The clone died minutes after birth.

Scientists in Australia are using sophisticated cloning technology to implant nuclei from an extinct frog into the eggs of another frog species. Results of the research were detailed to the same audience Temple addressed earlier this month.

Researchers are looking into other ways to bring back species, too.

"Conservation biologists are a bit concerned that de-extinction might indeed have a destabilizing effect" on the efforts to protect and restore species, Temple told the gathering in Washington.

The event in Washington at the headquarters of National Geographic was a TED talk, the nonprofit symposiums devoted to experts delving into important ideas in front of a live audience.

TED started in 1984 as a conference with the idea of attracting people from the fields of technology, entertainment and design. It has morphed well beyond that today, and the reach of speakers and their ideas are magnified the by Internet.

National Geographic's April cover story is also devoted to de-extinction.

The Washington event was independently organized, as some TED talks are.

In this case it was the idea of Stewart Brand, founder of the Whole Earth Catalog and a proponent of de-extinction.

His foundation is helping to underwrite the work of scientists, including those from Harvard University and the University of California, Santa Cruz, to take genetic tissue from dead passenger pigeons and over time re-create an entirely new population.

Battling to save species

In an interview, Temple said he doesn't necessarily oppose research that could lead to a rebirth of an extinct species - but he wouldn't advocate for it, either.

He recognizes, however, that de-extinction could help conservationists wage an offensive in what's been an uphill fight against the loss of species.

In his TED talk, Temple raised several concerns:

• With new technologies, those who are "inconvenienced" by efforts to protect endangered species might argue that a bird or a plant could simply be reintroduced later. That could be a problem since conservationists can have a hard time persuading the public to make sacrifices, such as protecting critical habitat, to protect a threatened species now.

• Bringing back a species that has been extinct for a long time could potentially harm the biological community where it is returned. That ecosystem has essentially moved on and established a new equilibrium without it.

• Species that re-emerge from extinction might require substantial attention to keep them viable - something Temple described as "conservation dependency," which could tie up limited resources.

In an interview, he noted that the reintroduction of the whooping crane in Wisconsin in 2000 hasn't been an overnight success.

"It's going to be a very long time before we . . . are able to sort of step back and let the species take over on its own," Temple said.

Such struggles don't stop people from dreaming about trying to bring back what they've lost.

Passenger pigeons once flew in gigantic flocks that were known to blacken the sky. But their proclivity to swarm together also made them easy targets for humans. They were hunted to extinction. The last known passenger pigeon died in a zoo in Cincinnati in 1914. The last well-documented passenger pigeon in Wisconsin was in 1899 near Babcock in Wood County.

"There is a sense of deep tragedy that goes with these things - and it's happened to lots of birds that people loved," Brand said at his TED talk.

"The fact is that humans have made a huge hole in nature in the last 10,000 years," he said. "We have the ability now, perhaps the moral obligation, to repair some of the damage."

If de-extinction takes hold, Temple suggested that a new field of science could emerge. Experts in "resurrection biology" could be called on to help determine the most viable candidates and most suitable habitat for them to live.

Temple said the passenger pigeon wouldn't be a good candidate.

It lived in a complex social structure and its strength was in its massive numbers, which would be impossible to duplicate.

He suggested a better choice would be the ivory-billed woodpecker, which lived in the bottomland hardwood forests of the southern United States.

There have been various sightings of the bird in recent years, but the observations have not been confirmed.

He said the birds are solitary and don't migrate, which would help humans keep tabs on the born-again bird. Also, the habitat is better today and there are more protections in place.

0 Comments